Why buy crewed submarines at all? What role do they play in protecting Australia’s interests now and into the future?

By James Goldrick (Australian National University)

The Australian government this week committed to spending A$50 billion on a fleet of 12 new submarines, contracted to French company DCNS and to be built in South Australia.

But how will these submarines meet with Australia’s strategic requirements, particularly beyond 2030, when the first of the new submarines will become operational?

Some have suggested that autonomous submarines might become more prevalent in the future, and may be a more cost-effective option. Others have argued that the large expensive DCNS submarines may be obsolete by the time they come on line.

Why buy crewed submarines at all? What role do they play in protecting Australia’s interests now and into the future?

Projecting uncertainty

Among the long-standing priorities in Australia’s defence strategy are protecting critical lines of trade and communication for essential national transport and military operations, and denying the use of the sea to a potential adversary.

Because of their unique characteristics, submarines will play an essential role in these endeavours. Their ability to restrict the actions of any would-be aggressor in the maritime domain remains unmatched. And despite the rate of technological change, they are unlikely to be challenged for at least a generation.

Submarines have the ability to operate covertly for extended periods and to attack with devastating lethality without warning. This means they can create uncertainty in the mind of an adversary about where they are and whether it is safe to sail ships or submarines. And the larger the submarine force, the greater that uncertainty.

Their stealth has a pre-conflict value too. In times of tension, such uncertainty can be a vital inhibitor to a would-be aggressor. Submarines can also be used to gather information about other countries’ capabilities or intentions, providing early warning of an attack.

Submarines can also be used for strike missions, including inserting special forces ashore to target enemy facilities. Submarines equipped with land-attack missiles can also be an effective means to target onshore facilities and this capability may be an option for Australia in the future.

Local waters

According to the government’s 2016 Defence White Paper, around half the world’s submarines will be operating in the Indo-Pacific region by 2035.

There are good reasons for this growth in regional forces and they apply to Australia as well. Australia’s geography and vast areas of strategic interest further shape the operational roles of our submarines, which in turn determine the required numbers, capabilities, endurance and size.

Asia will see even more submarines go to sea in the next few decades. Any maritime rivalries will inevitably have an underwater dimension. An effective submarine fleet adds greatly to a nation’s military weight.

There is no current substitute for the capabilities that submarines deliver in maritime warfare, and maritime warfare capabilities are important for Australia.

Listen in

While there are claims about the increasing vulnerability of submarines to detection, these must be balanced against the realities of the environment.

The sea is not yet transparent.

The Indo-Pacific sea areas are generally extremely challenging for acoustic sensors, whether passive or active. Other mechanisms for detection are much better at localising a submarine after its approximate position has become known than they are at achieving initial contact.

It is clear that the emerging technologies of unmanned vehicles and pre-positioned sensors will make it more hazardous for submarines to enter certain areas, particularly those close to well-protected enemy bases.

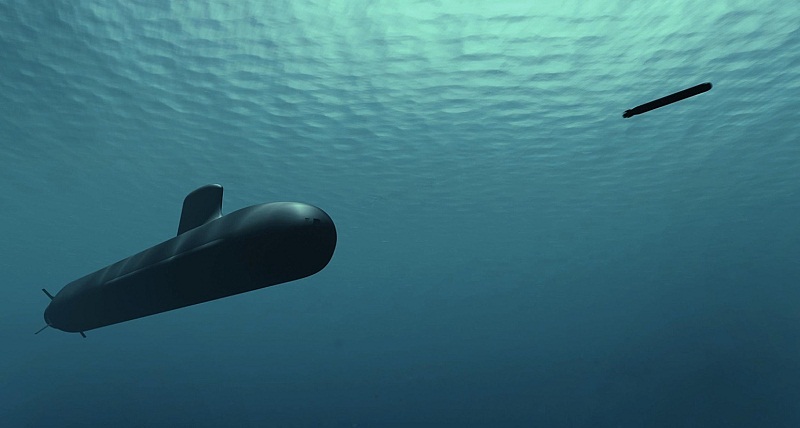

In turn, submarines are likely to employ unmanned vehicles (including air and even surface units) as their own “agents of influence and action” by sending them into the most high-risk areas to report or even attack.

In high intensity conflict with the threat of cyber-attack, the more valuable will be the ability to control such “local” networks of unmanned vehicles and operate independently of remote sensors and command and control systems.

No drone, particularly one that is fully autonomous and not reliant on external direction, can presently match a submarine’s combination of lethality and covertness. Nor can they match the situational awareness and intelligent decision making possible with a human crew. This is unlikely to change in the short- or medium-term.

These considerations shape Australia’s requirements for its submarines. They must:

- be in sufficient numbers to provide sustained operational availability

- be fully interoperable with allied forces, particularly those of the United States

- have very long range and endurance

- be sufficiently covert

- have excellent sensors and armament to overcome sophisticated threats, and

- be able to operate in tropical waters.

They should also have the capacity to carry and support unmanned vehicles in order to take advantage of this emerging technology.

Propulsion

Submarines are inherently complex. The design requirements for engines, power, fuel, weapon (and unmanned vehicle) capacity and provisions shape hull size and affect the numbers of people needed to operate the boats.

They need to be balanced against each other even more carefully than in surface ships. Any errors in calculating the parameters can be disastrous.

This was recently demonstrated when the Spanish Navy was forced to halt construction of its new boats and begin an extensive reworking of their design to overcome an 80 ton deficiency in their buoyancy.

A key distinction between submarines is their main power source for propulsion. Nuclear-powered submarines have the ability to operate for extended periods underwater and at high speed without the need for refuelling.

Diesel-electric submarines, by comparison, are slower although they can achieve very fast “burst” speeds for limited periods underwater. They also need to recharge their batteries at intervals, requiring the use of noisier diesels and access to air.

During these periods, they are at much greater risk of detection, whether from sensors “listening” for their machinery, or by radar (or even visual) contact with their schnorkel (air mast).

Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) systems have been developed. The German contender beaten out by DCNS used this system.

But AIP systems take up space and weight and generally provide greater submerged endurance only at low speed. They also use special fuels, which may require specialised facilities to replenish.

In theory, nuclear submarines’ superior speeds, unlimited endurance and ability to remain submerged indefinitely make them extremely attractive for a country with Australia’s strategic requirements.

However, apart from being much more costly than diesel-electric boats (probably well over twice as much per unit, assuming the same sensor and weapon fit), the acquisition of nuclear boats is not feasible for Australia at this time.

That’s because of the range and cost of their support systems – which the country does not possess. Unlike every current nuclear submarine operator, there is no domestic nuclear power industry.

Having to meet the operational requirements with a conventionally propelled boat thus makes a unique, tailored-for-Australia design the only option for our navy, while conventional propulsion is a key factor in our wanting greater numbers in order to achieve the necessary operational effects.

![]()

The author, James Goldrick, Adjunct Professor in naval and maritime strategy and policy, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation