Navigating Challenges to return Pakistan aligning to the vision of its founders

By Syed Atiq ul Hassan, Sydney Australia; 2 May 2024

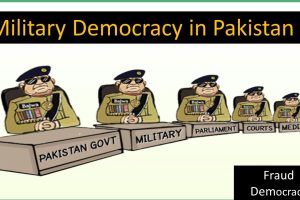

[In contemporary Pakistan, key institutions such as the military, judiciary, law enforcement, and bureaucracy have undergone significant politicization. This trend has led to a departure from

the visionary ideals of the nation’s founders, with political and religious parties, alongside bureaucratic and military interests, exerting considerable influence. The prevailing system operates more akin to a corporation, where democracy appears superficial and controlled by those in power, rather than a genuine expression of the people’s will.

This disconnects between the aspirations of the populace and the actions of those in authority has blurred Pakistan’s path, casting doubt on its true trajectory. To truly understand Pakistan’s current challenges, it is crucial to delve into the deep-seated roots of its systemic failures across various domains of governance and state dynamics.]

The military’s dominance in Pakistan’s political landscape has been pervasive since the country’s inception. Through a series of coups and behind-the-scenes manoeuvres, the military has effectively controlled key aspects of governance, shaped policies and perpetuating its own interests.

Will Pakistan and its nation ever find a pathway to the objectives of the resolution of Pakistan? Can Pakistan ever establish a true democratic governance without the military intervention? This has remained the questions of political analysts, intellectuals, and patriotic leaders, today.

Let’s rewind the 76 years old history of Pakistan, investigate, and analyse how and who governed Pakistan since 1947 and how Pakistan is now at a crucial stage, no easy way to put the governance on track that can flourish Pakistan with strong economy, military power, high technology, and strong and true political system.

Close to the creation of Pakistan, in 1946, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, while addressing at the Islamic College Peshawar says; “We do not demand Pakistan simply to have a piece of land, but we want a laboratory where we experiment on Islamic Principles”.

In the first address to the newly Constituted Assembly, Quaid-e-Azam in his opening words said, Assembly had two tasks, writing a provisional constitution, and governing the country meantime. He continued with a list of urgent problems: Law & order, so that life, property, and religious beliefs are protected for all.

Addressing to the role of arm forces, Quaid-e-Azam says, “Do not forget that the armed forces are the servants of the people. You do not make national policy; it is we, the civilians, who decide these issues and it is your duty to carry out these tasks with which you are entrusted.”

Addressing to the civil servant or bureaucracy in Peshawar on 14 April 1948, Qaid-e-Azam said, “Do your duty as servants to the people and the state, fearlessly and honestly.” He said, “governments are formed, governments are defeated, prime ministers come and go, ministers come and go, but you stay on.”

Quaid-e-Azam called upon politicians to desist from exercising political pressure on civil servants as “it only leads to corruption, bribery and nepotism.”

After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the 12-Points Objectives resolution of Pakistan was drafted by the first Prime Minister of Pakistan, Liaqat Ali Khan and was approved by the assembly on 12 March 1949. On approval from the assembly, Liaquat Ali Khan called it “the most important occasion in the life of this country, next in importance only to the achievement of independence“. Without going the list the 12 points, the resolution proclaimed that the future constitution of Pakistan would not be modelled entirely on a Western democratic pattern but on the ideology of democratic faith of Islam. Unfortunately, not a single point of that resolution could be implemented by any military or civil government since its creation.

On 9 January 1956 the draft of the first Constitution of Pakistan was presented by then Prime Minister, Choudhary Muhammad Ali (a Bengali parliamentarian) and was passed by the Assembly on 29th of February 1956. The assent was given on the constitution by the Governor General on 2nd of March 1956. This Constitution provided a Parliamentary form of government with the executive powers to the Prime Minister. President would be the Head of the State for 5 years and to be elected by all Members of National and Provincial Assemblies.

Unfortunately, the British empire transfer civil rule to the political leadership of Pakistan on 14 August 1947 but not the freedom to the military of Pakistan.

On the name of establishing Pakistan’s defence system, the British General Frank Messervy was given the charge of Pakistan Army as the first Commander-in-Chief when Pakistan was only few hours old that is on 15 August 1947. General Messervy continued as army chief until 10 February 1948. Then another General Sir Douglas David Gracey, who served British Indian army was taken over the charge as next army chief of Pakistan on 11 February 1948. He remained the army chief until 16 January 1951.

Then the first Pakistani major general Ayub Khan appointed as the first Pakistan army chief of Pakistan. Prior to his appointment as army chief, Ayub Khan joined Pakistan army from the Indian army and posted as a major general in East Pakistan. General Ayub Khan received his military training at the Royal Military College Sandhurst (UK). Hence it was but natural that General Ayub Khan’s loyalty was remain with British Army. General Ayub Khan remained the army chief from 23 January 1951 to 26 October 1958. Then he imposed the first martial law in Pakistan on 27 October 1958.

The influence of British army since the creation of Pakistan can also be validated to the fact that Pakistan first army chief General Sir Douglas David Gracey was not comfortable with the first Director-General of Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) major general (a Pakistani) Syed Shahid Hamid (14 July 1948 to 20 June 1950), and he was replaced by a British Major General Robert Cawthome as Director-General ISI on 20 June 1950 and he remained the ISI chief in 1959.

Prior to Ayub Khan’s (first) martial law in the country there were seven prime ministers ruled the first democratic period in Pakistan from Liaqat Ali Khan (14 Aug 1947 to 16 Oct 1951) to Feroz Khan Noon (16 Dec 1957 to 7 Oct 1958).

Since 1947 to 1957, the parliament had been in unstable status as there were many issues raised by the representatives (Bengali Politicians) of the East Pakistan who were in the majority in the house. The Bengali language acceptance as national language beside Urdu, the fair and equal distribution of treasury budget between East and West Pakistan, the balance of defence personals from East and West Pakistan, the fair distribution of ministerial portfolios between East and West Pakistan, the fair and equal positions in the bureaucracy of the state (East & West) and so on. Therefore, smooth running of parliament under the leadership of Prime Minister was just in turmoil. The Governor General Iskander Mirza announced emergency in East Pakistan in 1957 and asked General Ayub Khan to control the rising public protest and agitation demanding equal rights to the people of East Pakistan.

In 10 years, seven prime ministers have been changed through no confidence votes. The representatives of the East Pakistan shown their displeasure how the democratic system unfairly running the business affairs of the East and West Pakistan. Muslim League was losing control where Awami league support in East Pakistan was rising.

On 7 October 1958, Governor General Iskandar Mirza appointed General Ayub Khan as Chief Martial Law Administrator and Aziz Ahmad as Secretary General and Deputy Chief Martial Law Administrator. Then 1956 Constitution was seized, the democratic parliament was removed, and Martial Law was imposed in the East and West of Pakistan. The people of West Pakistan welcomed the Martial Law, distributed sweets on the street of Lahore and Rawalpindi, on the other hand, people of East Pakistan did not accept the Martial Law and continued their struggle for their demanded rights.

Military coups, such as those led by Ayub Khan in 1958, and Zia-ul-Haq in 1977 and then seized of civilian government and took the control of the government by General Pervez Musharraf as Chief Executive from 1998 to 2001, resulted in the suspension of democratic processes and the imposition of military rule. The military rule saw the suppression of dissent, curtailment of civil liberties, and censorship of media, all in the name of maintaining stability and national security.

In addition to direct interventions, the military has exerted influence through covert operations and alliances with political parties. The Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) has been accused of meddling in domestic politics, manipulating elections, and supporting proxy groups to further its strategic objectives.

The military’s control over key institutions, including defence, foreign affairs, and economic policy, has enabled it to wield significant power behind the scenes, often at the expense of civilian governance and democratic norms since the creation of Pakistan.

The military has employed various tactics to maintain its grip on power, including:

Censorship and Suppression: The military has often resorted to censorship and suppression of dissent to stifle opposition voices and maintain control over the narrative. Media outlets critical of the military have faced censorship, intimidation, and even closure, limiting freedom of expression and independent journalism.

Manipulation of Elections: The military has been accused of rigging elections using civil administration and manipulating the electoral process to ensure favourable outcomes for its preferred candidates or political parties. This has involved everything from voter intimidation and harassment to tampering with ballot boxes and falsifying results.

Co-optation of Political Parties: The military has cultivated alliances with political parties and leaders deemed sympathetic to its interests, providing them with support and resources in exchange for loyalty and cooperation. This has allowed the military to exert influence over the political landscape without directly assuming power. Without going to the history of rule in Pakistan from 1971 to the current government in power. The establishment directly through Martial Law or a customised democracy by installing their made politicians.

It’s fascinating to observe how advancements in technology, particularly in communication and information sharing, have reshaped societies around the world, including Pakistan. The prevalence of modern tools like smartphones and access to the internet has empowered the younger generation with unprecedented access to information and global events.

With over 60 percent of Pakistan’s population being youth, this demographic holds significant potential to drive change and shape the future of the country. The advent of social media and online platforms has democratized information dissemination, making it challenging for authorities to conceal their actions or agendas from the public eye. In the past, political machinations and hidden agendas could often go unnoticed, but today, transparency is increasingly becoming the norm.

Indeed, the rise of social media and online communication has fundamentally altered the dynamics of governance and public discourse. People are now more informed and connected than ever before, enabling them to participate actively in shaping their society and holding their leaders accountable. This shift towards greater transparency and openness has the potential to foster a more accountable and responsive political system in Pakistan and elsewhere.

The Political Ascendancy of Imran Khan: A Modern Approach to Pakistani Politics

The emergence of Imran Khan as a prominent figure in Pakistani politics heralds a new era marked by the intersection of modern technology, democratic ideals, and the aspirations of a dynamic youth population. Leveraging his celebrity status as a former cricket star and philanthropist, Khan adeptly harnessed a variety of contemporary technological tools to engage both the younger generation and established political constituents across Pakistan.

Utilizing his renown from cricket and philanthropy, Khan effectively employed social media platforms, online campaigns, and digital outreach initiatives to connect with diverse segments of society nationwide. His strategic use of technology not only resonated with the tech-savvy youth but also facilitated communication with traditional political supporters, thereby broadening his appeal and strengthening his political movement.

Imran Khan’s journey to political prominence owes much to his resonance with the country’s youth. Capitalizing on his charisma and widespread appeal, Khan tapped into the frustrations of young voters disillusioned by entrenched corruption and dynastic politics. Through his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party, Khan championed anti-corruption and pro-democracy reforms, striking a chord with a generation yearning for change.

One of Khan’s notable achievements is his ability to galvanize a diverse coalition of supporters, ranging from urban youth to educated professionals and disenfranchised segments of society. His grassroots organizing and strategic use of social media platforms facilitated widespread mobilization and contributed to the broad-based appeal of his political movement.

Today, a significant portion of Pakistan’s youth regard Imran Khan as a Murshid (Mentor), crediting him with raising awareness about the intricacies of Pakistani politics and challenging the prevailing narrative propagated by traditional elites. Khan’s leadership has sparked a newfound interest and engagement in political affairs among the younger generation, reshaping the political landscape of the nation.

Despite facing formidable opposition from established political parties and other powerful institutions, including the judiciary and bureaucracy, Khan has weathered numerous challenges, including a barrage of false accusations aimed at undermining his credibility. However, his popularity and grassroots support continue to expand, underscoring the enduring appeal of his message of reform and accountability. In conclusion, Imran Khan’s ascent in Pakistani politics represents a paradigm shift towards a more inclusive and technologically savvy approach to governance. While his journey has not been without obstacles, Khan’s ability to connect with diverse segments of society and his unwavering commitment to reform mark him as a transformative figure in the contemporary political landscape of Pakistan.

The last general elections on February 8, followed by subsequent by-elections, serve as a glaring example of the failure of the traditional approach of the Pakistani establishment in managing elections, exposing their shortcomings on both local and international fronts. International monitors and media closely observed the February 8 elections and widely reported instances of significant rigging and fraudulent practices.

It’s imperative for the establishment to recognize the evolving global landscape, where realities and issues can no longer be concealed from the public eye. Presently, the judiciary, law enforcement agencies, and the establishment have seen a decline in their credibility among most Pakistanis. Meanwhile, the state’s functions are faltering, leading to a looming financial crisis, dwindling trade and exports, escalating foreign debts, and heightened concerns from adversaries on both borders.

Given this precarious situation, urgent action is required from the establishment to salvage Pakistan’s future by rebuilding trust among the populace. This entails acknowledging the current ground realities and instilling confidence in the educated and skilled individuals who are increasingly leaving Pakistan. The establishment must engage in constructive dialogue with those elected by most of the Pakistani people, as failure to do so could lead to disastrous consequences, akin to the events that led to the fall of East Pakistan.

While Pakistanis are steadfast in their desire to prevent further disintegration of the country, the situation in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) is alarming. Unlike East Pakistan, the people of KPK possess a distinct culture and outlook, and their proximity to Afghanistan, where India is alleged to support terrorism against Pakistan, adds to the complexity. If the grievances of the followers of Imran Khan especially in KPK are not addressed, there’s a risk of unrest that could jeopardize Pakistan’s unity, as witnessed in 1971.

It’s essential for the establishment to heed these warnings and take proactive measures to address the concerns of all regions and communities within Pakistan, thereby safeguarding the integrity and stability of the nation. (The writer is a Sydney-based journalist, political analyst, writer and a commentator. He is an editor, Tribune International, Australia. His email is shassan@tribune-intl.com ).

END