By Prachi Salve

In a country where “inclusion” is the emerging political mantra, an estimated 215 million Indians–roughly the population of Canada and Pakistan combined–are largely excluded from economic progress.

After the Aam Aadmi Party’s sweep to power, riding on the support of Delhi’s poorest, these huge numbers also provide an indication of the political space available for parties that focus on those excluded from economic growth.

43 million households have zero assets, according to census data. If we consider an average of five people living in a household, that gives us a figure of 215 million Indians without assets.

Of those with zero assets, nearly 80 million people—the population of Germany—or 16 million households are Adivasi.

Adivasis, or “original dwellers”–a collective term used for some of India’s diverse tribal groups–are the most excluded group in India on almost all social counts, such as education, housing, land-ownership and access to government programmes.

On most counts, other disadvantaged groups–Dalits, Muslims and women–are better off. Less than 60% of Adivasis are literate–more than 13% lower than the national average–and only 40% live in pucca (solid) houses, 53% below the national average.

Ban Ki-Moon, secretary general of United Nations, and Jim Yong Kim, president of the World Bank recently expressed concern about India’s excluded millions.

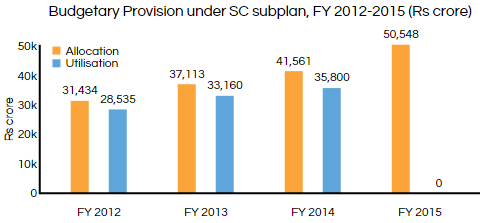

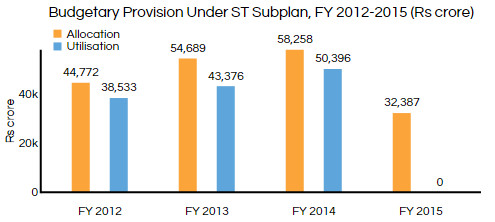

Worse, the government has not been spending the money especially set aside for the advancement of groups chosen for affirmative action, such as scheduled castes (SC) or Dalits and scheduled tribes (ST), which includes adivasis.

Many allege that state governments are using these funds for other purposes.

In 2014-15, Rs 82,935 crore ($13 billion), was the budget for programmes aimed at improving the quality of life for SCs and STs.

Exclusion is the process by which individuals and population groups face barriers in relation to their access to public goods, resulting in social and economic inequity, lowered capabilities and adverse justice and dignity outcomes.

These barriers occur due to social- and state-sanctioned discrimination, dispossession and cultural biases.

Of the four groups, since data is available uniformly only for Dalits and Adivasis, let us look at these groups’ socio-economic nature.

India has 201 million SCs and 104 million STs, divided into 41 million and 21 million households, respectively.

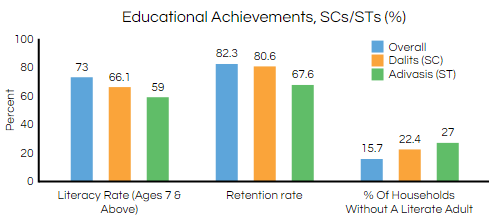

Adivasis occupy nearly all the lowest rungs on the education ladder.

When we look at the retention rate (calculated as enrolment in grade V in a year, as a proportion of enrolment in grade I four years ago), adivasis have the lowest rate at 67.6%.

Adivasis also have the highest percentage (27%) when it comes to households without a literate adult.

Let us now look at housing.

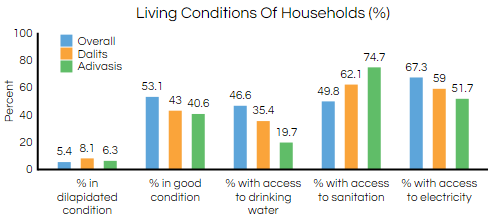

Dalits/adivasis continue to be the most excluded group when it comes to housing. As against the national average of 5.4% of households living in dilapidated homes, the proportion is 8.1% for dalits and 6.3% for adivasis.

Access to drinking water is at a low of 19.7% for adivasis, against the overall percentage of 46.6%.

The only silver lining here is access to sanitation: nearly 75% of adivasi households have it, against the national average of 49.8%.

Exclusion from land

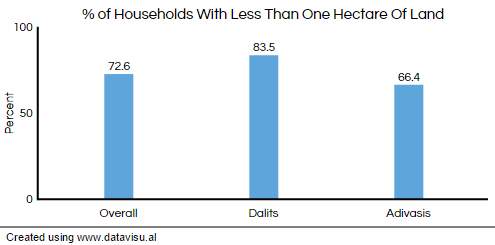

The majority of excluded groups own less than 1 hectare of land. While 83% of dalit households own 1 hectare, the ratio is 66% for adivasis.

The government has separate budgetary provisions for SC and ST communities. However, funds meant for social welfare are often diverted for other purposes or have not been utilised, as the chart below reveals:

Allocation for the SC/ST programme has increased 9% during the last four years, from

Rs 76,206 crore ($12.2 billion) in 2011-12 to Rs 82,935 crore ($13 billion) in 2014-15. However, utilisation dropped from 90% to 86% for SCs.

This article was originally published in IndiaSpend.