“Women in the Media have come a long way and are inspiring example for next generation”

Women now account for more than 56 per cent of all journalists in Australia, surveys indicate

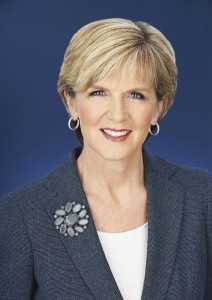

Foreign minister Julie Bishop remarked in her speech that Australian women in media have come a long and have even reached to the top levels of the political reporting class. Women participation in the media offers a platform for leadership and confers empowerment as women have an opportunity to make their voice and opinions heard more broadly.

Australia’s only female cabinet minister Julie Bishop is determined to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment under three pillars: women’s leadership in families, communities, in business, in public office, women’s economic empowerment, and ending violence against women and girls.

“Tackling the barriers to female participation – including by providing much better access to education – that’s the key, that’s the pathway to progress” she says. Australia has made a commitment to equality between women and men and “must continue to take a leadership role in terms of female empowerment within our communities and within our workplaces, and that includes within our media.”

The text of her speech at National Press Club, Canberra ACT is as follows:

I am absolutely delighted to speak at this inaugural event for the ACT chapter of the Women in Media network. I also want to acknowledge others involved in the initiative, particularly Katherine Murphy, Eliza Borrello and the national patron – the wonderful Catherine Jones. What a fabulous gathering of women here today and I would love to acknowledge every single one of you but I’ll just pick out one for the moment – Margaret Reid – a particular friend and supporter of mine, so thank you very much Margaret for being here.

I note that the title of this network is sufficiently flexible to include those who work in the media as well as those who sometimes appear in the media. So today I will focus on both.

It is a challenging time for the media sector in general with the internet spawning a plethora of disruptive technologies. On Twitter, news articles are reduced to 140 characters and published instantaneously without the need for subeditors or the usual channels of publishing – although most of us would be grateful for a Twitter subeditor from time to time! Some bloggers attract followings that rival the readership of news articles, while the news websites themselves are cannibalised for their content by other sites that compile content.

Social media, and the advertising takeover by the internet and other digital platforms, have prompted the most fundamental structural change in the media sector in a century.

But another fundamental change has happened at the same time – a quieter revolution, maybe, that not as many people have noticed. In the space of the last generation, at least in this country, women have been attracted to careers in the media at unprecedented levels.

Recent surveys have indicated that women now account for more than 56 per cent of all journalists in this country – almost doubling from just two decades ago.

However, the same surveys have found that women are overrepresented in lower paid and lower status positions, with the majority of senior editorial and managerial positions still held by men. This is partly due to experience, as research shows the average age of male journalists is just over 40 years of age, while the average age of female journalists is 34 years. With increasing numbers of women graduates with journalism degrees, pressure will continue to build within the industry for cultural change.

While it is greatly disappointing that gender and age discrimination continues in workplaces, there are many women pushing boundaries and refusing to accept the limits placed by others on their career aspirations. My mother was my greatest inspiration and I recall her words to me and my two sisters – you can do anything, nothing should be off limits, follow your dreams. This is advice I often give to young women and I would certainly offer it to any young woman embarking on a career in the media.

Women in the media have come a long way. Imagine the cultural and attitudinal barriers in the way of international media stars like Barbara Walters, who first appeared on the US Today Show in 1962 along with Diane Sawyer who also began her career around that time.

I suggest a key area that must change is that Australians rarely see a female face over 60 on our nightly news broadcasts, whereas older males are far more common. There are of course exceptions, and I was in Perth over the weekend for Telethon, and the fabulous Susannah Carr was there – a nightly newsreader on Channel 7 in Perth and she’s doing a wonderful job.

In the Canberra Press Gallery, there have been for long, long years women who have broken through to the top levels of the political reporting class. Michelle Grattan leads the charge – and others in the print/ online media – Stefanie Balogh, Laura Tingle, Latika Bourke, Samantha Maiden, Katharine Murphy, Tory Shepherd, Jacqueline Maley (thanks for the article Jac), Lenore Taylor, Fleur Anderson among others.

In broadcasting – Karen Middleton, Fran Kelly, Lyndal Curtis, Alison Carabine, Laura Jayes. In photography – Kym Smith, and national commentators – Jennifer Hewitt, Janet Albrechtsen, Niki Savva, Annabel Crabb – I could go on and on and I wish I had time to name them all, for women in the media today are inspiring by example the next generation of women to pursue careers in media.

As for women in Canberra who appear in the media from time to time, all sides of politics have female representation including within the leadership ranks. I am very proud of the 25 Coalition female Members and Senators – who are competent and effective representatives – making ministerial contributions, our Speaker in the House of Representatives, those chairing Joint Standing Committees in the House and the Senate, those acting as Government Whips and other roles and all have a story to tell of their journey to this place.

And I acknowledge the presence here today of the Prime Minister’s chief of staff Peta Credlin who is launching tonight a Coalition female staff network and I also acknowledge, all my female advisers and staff over at this table who have left the boys back in the office to fend for themselves for an hour or two!

In my field of international relations it has been a slow start for women. The truth is: over the centuries, state-to-state diplomacy has been an almost exclusively male affair – unless you include Cleopatra! I suspect Catherine of Aragon was the first recorded woman diplomat in the history of diplomacy in the sixteenth Century.

There was actually a significant work published this year on the topic of women in diplomacy by Helen McCarthy entitled: Women of the World – The Rise of the Female Diplomat.

As she noted, at the Congress of Berlin in 1878 – when the European powers came together to redraw the political geography of the Balkans after the Russo-Turkish War – women were “witness to history, not history makers.” Women were present, but their roles were firmly, and formally, circumscribed – as queens, princesses, aristocrats, wives, daughters, mistresses.

Only during the wartime shortages of the First World War did women breakthrough in informal and ad hoc diplomatic roles. British Arabist Gertrude Bell was pivotal in Britain’s prosecution of that war, through her unique diplomatic, intelligence and analysis role in the Middle East, although Helen McCarthy describes Bell’s appointments as “feminine islets in a vast sea of male authority”. McCarthy also writes about Alexandra Kollontai – who, in February 1924, when Norway recognised the Soviet Union – became the world’s first female head of mission.

In the period after the Second World War, the barriers – including the marriage bar that deemed a woman’s use-by date had been reached the moment she had a husband – slowly began to fall. Australia had our first female Trade Commissioner, Beryl Wilson, in 1963. Our first female career diplomat appointed as an ambassador was Ruth Dobson to Denmark in 1974. And she was only just pipped as Australia’s first female head of mission by Dame Annabelle Rankin, a political appointee to New Zealand in 1971. Mind you it did take us 113 years to appoint a female as Foreign Minister.

Gradually, over decades, in countries all around the world, women have penetrated deeper and deeper into diplomatic ranks. The United States has had three outstanding female secretaries of state – John Kerry joked to me recently that the US State Department was worried whether it could now bring itself to work for a male Secretary of State!

Having just passed my first anniversary in office, I am greatly impressed by the quality of Australia’s female diplomats. Our Head of Mission in Baghdad, Lyndall Sachs is doing an extraordinary job in the difficult work environment in Iraq. Frances Adamson heads our vital post in Beijing. Louise Hand is in our Ottawa mission. Jean Dunn in Poland played an important role during the MH17 events in Ukraine. Deborah Stokes heads our post in Port Moresby and we have appointed Gillian Bird, currently Deputy Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to the prestigious United Nations post in New York for next year. And I hope there will be many more – including a female head of the Department of Foreign Affairs in due course and I acknowledge Jane Halton as the Secretary of the Department of Health here today.. Finance, I knew that! She was my Secretary when I was the Minister for Ageing, so I’m sorry, I still see you in that role!

The truth is: if you look at the state of gender equality in 2014, you would have to conclude that in many industries and sectors, particularly in developed countries, women have indeed come a long way. But I think – on any fair analysis – you would also have to acknowledge that significant barriers remain around the world. In a highly advanced, technological age, there are still more than three-quarters of a billion adults worldwide who can’t read or write. And nearly two-thirds of those 780 million illiterate adults worldwide are women.

Across most regions, that proportion has barely changed for the past 20 years – even as we have made such extraordinary progress in so many other areas.The United Nations estimates that the Asia and Pacific region loses US $90 billion in GDP a year because of women’s limited access to employment opportunities and another $US16 to $30 billion annually as a result of gender gaps in education. According to the World Bank, productivity per worker could soar by up to 40 per cent if we eliminated discrimination against women in the workforce.

Consider this: girls in Afghanistan complete primary school at approximately half the rate of Afghan boys – so primary school completion rates for girls are approximately 21 per cent, half that of boys at 40 per cent. And – according to the World Bank – female school enrolments in Mali for example are comparable to those in the United States in 1810.

The bottom line is: women’s equality in education and employment is still a big issue. It is an issue that is holding us back as a globalised world.

I want to frame this in a positive light for there is a huge potential economic and social dividend that will be derived from empowering women to become economic and community leaders. We know there is a clear link between economic growth and poverty reduction in developing countries. Anything we can do to boost economic growth will have flow-on effects for poverty reduction and that’s where we are targeting our aid budget. Tackling the barriers to female participation – including by providing much better access to education – that’s the key, that’s the pathway to progress.

I have set a number of benchmarks for our aid program including that 80 per cent of our aid investments – no matter what other impact they may have – must effectively address gender issues. For example, Australia’s development assistance in Afghanistan is targeted to help the effort to lift girls’ school enrolment from virtually zero under the Taliban to almost 3 million girls today.

I have determined that our aid programs, in the Pacific in particular, will promote gender equality and women’s empowerment under three pillars to reflect that there are persistent challenges and that progress towards gender equality has been too slow. First, women’s leadership in families, communities, in business, in public office, women’s economic empowerment, and ending violence against women and girls.

In this regard, I am a champion of former UK Foreign Secretary William Hague’s global initiative of combating sexual violence against women in conflict – a cause I am personally advocating.

In fact in the United Nations Security Council this week, Natasha Stott Despoja, whom we appointed as Australia’s Ambassador for Women and Girls last December – in fact only hours ago, represented me at the session on Women, Peace and Security and I received a joyous text from her this morning. Apparently her speech went over very well.

At the recent debate on 19 September at the UN Security Council on terrorism in Iraq and Syria, I noted the disproportionate attacks on women and girls and as I said at the time – “women and girls are bearing the brunt of this conflict as ISIL targets women, children and minorities for sexual violence and expectant mothers are forced to flee their homes” – and we provided an additional $2 million in assistance to support them.

Recently we brought together 30 Pacific female political leaders and senior bureaucrats to the inaugural Pacific Women Policy Makers’ Dialogue to promote strategies to enhance women’s leadership and decision-making to boost economic growth and raise standards of living.

Empowering women is not only the right thing to do; it is the smart thing to do.

I recognise that continuing barriers to female participation, around the world, represent a major impediment to higher global growth. As a nation, Australia has made a commitment to equality between women and men.

To help women in other nations, we must continue to take a leadership role in terms of female empowerment within our communities and within our workplaces, and that includes within our media.

During my travels to developing nations, I am careful to assure them Australia does not presume to lecture other countries or tell them how to run their governments or their societies but we can offer the benefits of our experience and our insights. I believe that those in the media also have a particularly important role to play in continuing to change attitudes and break down stereotypes.

I cannot speak at an event such as this without acknowledging that at present I am the only woman in Cabinet but I pay tribute to all the women who have been Cabinet Ministers in Australian Governments. The challenge I have set for myself is to do the very best I can to make it easier for those who will follow me. I feel that responsibility every day.

Your work in the media offers you a platform for leadership. It confers empowerment through the ability to have your voice and your opinions heard more broadly. And that raises the responsibility you carry to continue to advocate for change, both at home and abroad.

And women must learn to look out for each other. As Madeleine Albright famously said “there’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help other women.”

I wish you all the best as you develop this network – and help with the continuing task of finding new ways for women to contribute to the betterment of our society – for the empowerment of women is to the benefit of all.