By John Kemp

The South China Sea has become the most important testing ground for the changing economic, political and military relationship between China and the United States.

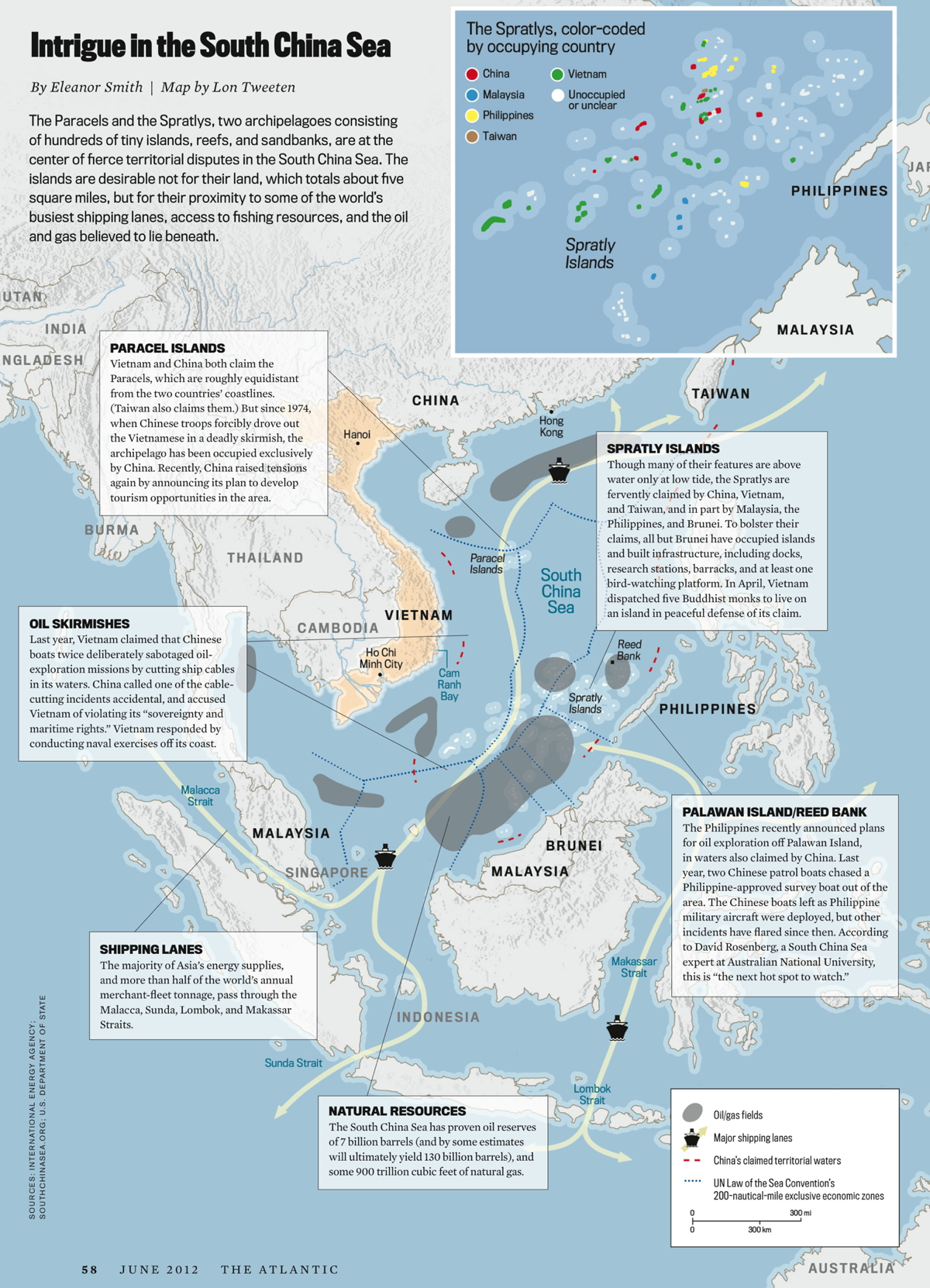

The islands, rocks, reefs and shoals at the heart of the dispute — most of them uninhabited and submerged at high tide — cover just a few square kilometers of a sea area that extends over 3 million sq. km. But long-festering disputes over sovereignty among the littoral states (principally China, Vietnam and the Philippines but involving Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia) have been transformed into a dangerous and unpredictable confrontation between the superpowers (China and the U.S.).

In theory, the dispute is straightforward and consists of three elements: (1) who owns the outcrops; (2) what rights, if any, does ownership confer to natural resources in the surrounding seas and beneath the seabed; and (3) what does ownership mean for ships and aircraft of other nations journeying through the area, which contains some of the world’s busiest and most important sea lanes.

China and the other littoral states dispute ownership (element 1) as well as the rights to resources and maritime control that flow from it (elements 2 and 3). The U.S. officially takes no view about ownership and control of resources (elements 1 and 2) but has a strong commitment to “freedom of navigation” and resists attempts to assert control over the surrounding sea (element 3).

Washington wants to freeze development of the outcrops and other activities it considers “provocative” pending a resolution of which country, if any, owns them and insists its ships and aircraft have the right to operate anywhere in the area. China says it owns the outcrops so is entitled to exercise full sovereignty over them — including construction of structures and land reclamation, as well as proclaiming territorial seas around them and claiming an exclusive economic zone.

The South China Sea is often made to seem like a technical legal dispute. But it is really a raw contest for power and influence between an incumbent superpower and a rising one. The South China Sea has become a combustible battle of wills between a status quo power (the U.S.) and a dynamic one that wants to rewrite the settlement produced at the end of World War II when it was largely powerless (China).

It pits a legalistic, multilateral model of dispute resolution based on international law (favored by the U.S.) against a bilateral approach based on diplomacy and military power (favored by China).

It raises questions about whether states can be bound by the decisions of international tribunals against their will (the Philippines has taken its dispute to arbitration but China has insisted it does not consent to the arbitrators’ authority).

In the military realm, it tests whether China’s naval power will be confined by the first island chain (Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines) or out into the heart of the Pacific Ocean.

By extension, it raises issues about whether China will remain primarily a land-based power or become a maritime power to rival the U.S. with operations across all the world’s oceans.

More generally, it raises questions about whether the U.S. is trying to engage China or construct a network of alliances across Asia and the Pacific to contain the country’s economic, political and military power. South Korea, the Philippines, Japan, Taiwan and Malaysia are in varying degrees allies of the U.S., which is also forging closer links with Vietnam, fueling China’s suspicions of encirclement.

And the South China Sea dispute has become entangled in the domestic politics of both countries. For China, it is about adjusting the postwar international framework to accommodate the country’s “peaceful rise” and recognize Beijing’s rights as a “big power” after centuries of humiliation at the hands of Western colonialists and Japan.

For the U.S., the dispute is entwined with fraught discussions about the country’s economic, political, diplomatic and military decline, whether the Obama administration should have taken a more robust approach to projecting U.S. power, and whether the next president should take a harder line with China, Russia and Iran.

Neither Chinese President Xi Jinping nor U.S. President Barack Obama can afford to display any weakness on the issue, which is a matter of national pride on both sides. So far, the two sides have opted for a strategy of controlled escalation.

China has accelerated land reclamation and is sending thousands of tourists each year on cruise ship tours to islands it claims. The U.S. has responded by flying a spy aircraft near some disputed outcrops to exercise its claim to freedom of navigation (complete with invited television crew to make the point clear).

China has hinted it could proclaim an air defense identification zone in the area, which would presumably mean its ships and aircraft would be more aggressive in challenging overflights by military and civilian aircraft.

There is a substantial element of theater in this conflict, which is being played out in front of the media and conferences: both sides want to appear strong in front of a domestic audience and their foreign allies while minimizing the risk of accidental confrontation.

To avoid accidents, the two sides have reached a military-to-military understanding on how to handle unplanned encounters at sea between their navies and sought to do the same for aviation after a series of hair-raising intercepts of U.S. military aircraft by Chinese fighters operating from the island of Hainan.

Both governments have notified the other in advance of publishing military strategy documents likely to draw media interest and stoke controversy.

Neither wants to jeopardize the wider relationship. On a wide range of issues from climate change, intellectual property protection, trade and cybercrime to the Middle East and the proliferation of sensitive military technologies, the two sides need each other.

China’s Xi has been invited to make a state visit to Washington later this year, which means both sides have a strong incentive to stress cooperation over confrontation in the overall relationship.

The problem is that both sides are still committed to a controlled escalation strategy, which could easily become an uncontrolled one if not carefully managed. The sheer number of actors in the South China Sea dispute increases the risk of miscalculation.

The U.S. appears to have only limited control over the activities of Vietnam and the Philippines. Manila is a U.S. ally, but Hanoi is nominally a communist government, though it enjoys increasingly close relations with the U.S. at the military-to-military level.

Commanders of individual aircraft and ships in the area have to make instant decisions in the case of unplanned encounters or unexpected behavior. In theory, local commanders can be controlled through strict protocols, but in practice those may not always work and military-to-military communications is poor.

In 2014, China’s close intercepts of U.S. military aircraft, which drew fierce protests from U.S. officials, were blamed on idiosyncratic military officers on Hainan. Whether this was true or was a matter of central policy remains unclear, but it points to concern about the level of centralized command and control over local military forces.

There is an urgent need to break the escalation cycle and find a better way to manage the disputes. International law, appeals for a freeze on the dispute, and other “norms” of international relations are not terribly helpful since the dispute is fundamentally about military power.

Rather than ratchet up the confrontation, hoping the other side will back down, both sides need to find some creative diplomacy to help transform the nature of the dispute and change the narrative before it becomes even more poisonous.

John Kemp is a Reuters analyst. This article originally appeared in Japan Times